starcraft and networking in the 90s (part 2)

This is the second post of a two-part series on Starcraft and late-90s networking. Part 1 describes Starcraft’s many connection options.

Configuring Starcraft networking in 1998 was an adventure. There were four different connection options (plus AppleTalk on Macintosh computers), each of which required specific software and hardware to function. How did anyone figure this stuff out?

It turns out that the Starcraft CD included detailed support documentation. Today, this provides a glimpse of computing history circa 1998.

Documentation on the CD-ROM

Why distribute documentation on a CD? In 1998, developers could not assume that everyone had Internet access. The fastest and most reliable delivery mechanism was to include the documentation on the CD itself.1

Upon mounting the Starcraft CD, users could find the documentation in the “help” directory. It was a full website, available both with and without HTML frames (a trendy feature in 1998). A footer on the bottom of the index page proudly claims that the pages are “JavaScript enhanced.” The files have a last modified date of March 3rd, 1998, which means they were likely written before StarCraft’s official release. Blizzard was trying to address the problems they expected players to have, perhaps based on feedback from their earlier multiplayer games like Diablo and Warcraft.

“Ask your salesperson”

Under the section titled “NULL MODEMS”, the documentation gives this advice:

Where do I find a “null modem” serial cable? Most computer supply stores stock cables appropriate for direct connect use. Ask your salesperson for a “null modem serial cable” or “laplink serial cable”

Computer stores were an important source of technical support in the late 90s. I remember spending many hours at stores like CompUSA and Fry’s as a child. The market was fragmented between many incompatible protocols, and the technology was constantly evolving. There wasn’t much information online yet, and people weren’t yet used to looking things up online anyway, so it made sense to ask in a store.

“Down for maintenance from time to time”

Battle.net was Blizzard’s game matchmaking service available over the Internet. Players could chat with each other and create or join games. However, in 1998 there was no expectation that online services would be available 24/7:

BATTLE.NET NOT RESPONDING

Battle.net is taken down for maintenance from time to time.

If you receive the error rarely, then chances are Battle.net is either actually down and will be running again shortly, or your connection to the Internet is very poor.

In either case, give it an hour or so and attempt to re-logon to Battle.net. You should succeed at that point.

“Give it an hour or so” would have been a familiar strategy for Internet users in the late 90s. Networks were being overwhelmed, and the underlying technology was much less sophisticated than it is today, so users often found themselves disconnected.

Blizzard likely anticipated that most multiplayer games would run over local area networks instead of battle.net. Users could still play if battle.net was down; they would just need to bring their computers to a friend’s house! Most players were doing this anyway, since the latency and reliability were so much better over a LAN than the public Internet.

“PCs that are in the middle of the chain are ‘routing’ machines”

One of the networking options in Starcraft was direct cable connection over a serial port. The Starcraft UI and user manual both claim that this supports up to 4 players, but things get dicey for 3-4 players:

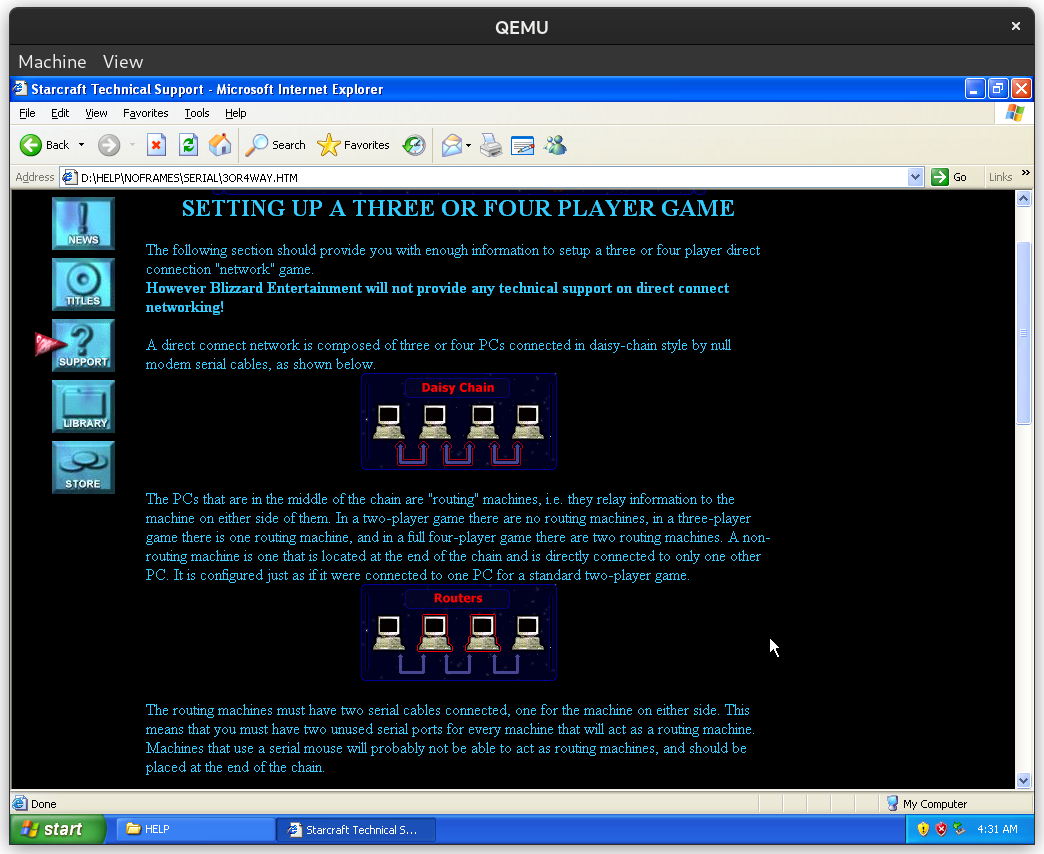

SETTING UP A THREE OR FOUR PLAYER GAME

The following section should provide you with enough information to setup a three or four player direct connection “network” game.

However Blizzard Entertainment will not provide any technical support on direct connect networking!

Once again, the responsibility to get things working falls on the users. Blizzard merely provides “information,” in the form of detailed technical descriptions and network topology diagrams:

This reads like an excerpt from Computer Networks: A Systems Approach. We learn that computers must be daisy-chained with serial cables, with the computers in the middle acting as “‘routing’ machines.” Additionally, users must choose the serial ports carefully. Due to a limitation in the “PC serial communications architecture”, each PC “shares two interrupt requests among the four devices… COM1 shares an interrupt (IRQ) with COM3, and COM2 shares an interrupt with COM4.” How many users, then or now, would know what an interrupt is?

“As the number of households with multiple networked computers grows”

If a home in 1998 had Internet access at all, it was usually through a single computer connected by a dial-up modem to a phone line. As far as I’m aware, ISPs would assign each computer a unique, public IP address. Few homes had a private network hidden by NAT; most home computers were directly addressable on the public Internet.

When each computer had a public IP address, it was relatively easy for Starcraft instances to connect over the Internet. Battle.net served as a matchmaking service, essentially allowing users to advertise their public IP addresses. Once the game started, clients would send each other UDP packets directly in a peer-to-peer topology.2

Blizzard knew this simple networking model was unlikely to last for long, but they did not know how to fix it. So they asked their players for help!

The use of proxies to connect computers to battle.net is officially unsupported by Blizzard. However we realize that as the number of households with multiple networked computers grows, proxies are becoming a popular inexpensive method of allowing multiple computers to gain access to the Internet. We will try to pass along as much information as possible to assist users in the setup of their proxies to allow play over battle.net. Most all of the proxy setup information we currently have was sent in by users like yourself.

If you are trying to setup your proxy software please note that Starcraft sends all information over port 6112.

If you are successful in configuring proxy software programs to work with Starcraft, please email support@blizzard.com details of the configuration settings so that we may help other customers in a similar situation.

Today, we know that there are two main ways to address this problem. The first is to configure port forwarding in the proxy, which users would have to do manually. This would work, but only for a single Starcraft client per LAN. The other approach is to use NAT traversal techniques like STUN, TURN, and ICE – however, those were not available in 1998.3

For Starcraft II, released in 2010, Blizzard switched to a client-server model, sidestepping the NAT traversal problem completely. Perhaps more importantly, this moved game state from player-controlled clients to trusted servers, making it much more difficult to cheat with a hacked Starcraft client.

“Invalid ICMP datagram fragments”

The Internet of 1998 was a safer place than it is today. Even so, allowing strangers to connect directly to your computer carried risks, as Blizzard discovered:

Important: It has come to our attention that certain users are taking advantage of security flaws in Windows 95 and NT to crash other users over the internet. Microsoft has released fixes for these flaws for both Win95 and NT. The fixes prevent most, but not all, of these programs from being used over the internet. Check Microsoft’s web page for more information on the security flaws and how to fix them.

Later, the documentation recommends searching for the terms “Out-of-Band” and “Invalid ICMP Datagram Fragment” to find the hotfix patch online. I believe this refers to the issue Windows NT and Win95 may hang when they receive invalid ICMP, which was a denial-of-service attack exploiting a bug in the Windows networking stack. By sending malformed ICMP packets to a target computer, an attacker could cause the entire machine to freeze.

Blizzard’s documentation plays down the risk: “Hackers and other people with malicious intent can take advantage of this flaw to crash systems. It is not harmful, but can cause this crash.” Microsoft’s security advisory also recommends waiting for the next service pack release of Windows instead of applying the hotfix immediately “unless you are severely impacted by this specific problem.”

The vulnerability was widely deployed and easily exploitable. Why the lack of alarm? I think the main reason is that computers and the Internet had not yet become central to the lives of most users. Computers were a tool for printing documents, editing spreadsheets, browsing the nascent web, and, occasionally, gaming. Even these activities occurred mostly offline. For most people, the important things – communication, commerce, social identity – did not yet involve the Internet. From this perspective, the stakes seem low. Who cares if some kids can’t play their games?

Conclusion

Starcraft was released at a pivotal time. The Internet was just starting to enter the mainstream; the dot-com bust was a few short years away. Users had to navigate a complex and fragmented landscape of networking technologies, which were often unreliable and slow. No one would have imagined that today, over twenty years later, players around the world would still be playing Starcraft online!

This has the fortunate side-effect of preserving the original documentation. While nearly every external link in the site has long since vanished from the Internet, anyone with the CD ISO can access the original documentation today. ↩︎

Dainotti, A., Pescapé, A., & Ventre, G. (2005, July). A packet-level traffic model of Starcraft. In Second International Workshop on Hot Topics in Peer-to-Peer Systems (pp. 33-42). IEEE. PDF ↩︎

STUN was standardized in RFC 3489 (published 2003), TURN in RFC 5766 (published 2010), and ICE in RFC 5245 (also published 2010). ↩︎